Troubadour International Poetry Prize 2020

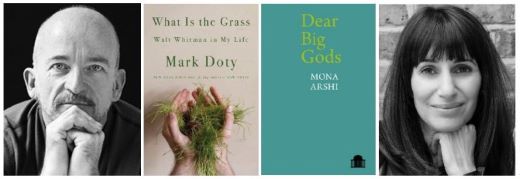

The following prizewinning poems were chosen by our 2020 judges, Mark Doty & Mona Arshi, & announced online at Troubadour International Poetry Prize Night on Mon 23 Nov 2020. (see judges reports & poems below)

- First Prize, £2,000, Entre-Deux-Mers, June, Amy Glynn, Lafayette, California

- Second Prize, £1000, Filter Queen, Michael Lavers, Provo, Utah

- Third Prize, £500, Calf, Elizabeth Cook, London

Commended poems:

- The Reed Flute & I, Abeer Ameer, Cardiff

- Drag, Alex Matraxia, Hadley Wood, Hertfordshire

- In the maternity wing, Ann Leahy, Dublin

- Anchorite, Christine MacFarlane, Bradford-on-Avon, Wiltshire

- Red Peppers, David Tucker, Dexter, Michigan

- Distance Runner, Giles Goodland, London

- Curfew, Hussain Ahmed, Oxford, Mississippi

- Secret Baptism, Jessica Cohn, Aptos, California

- The Tees Roll, Judi Sutherland, Malahide, Co. Dublin

- Mouth Game, Katie Hale, Penrith, Cumbria

- Born in the year of the boar, Maia Elsner, Oxford

- On Reading Olav Hauge, Margaret Wilmot, Polegate, E. Sussex

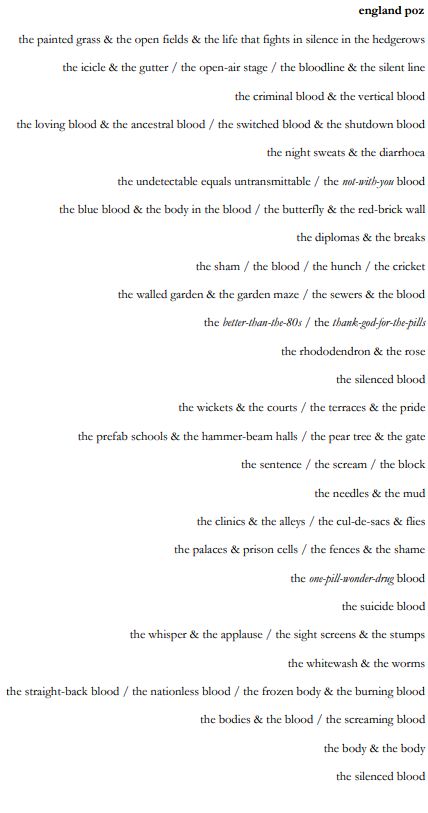

- england poz, Mark Chamberlain, London

- Crown Shyness, Mark Granier, Bray, Co. Wicklow

- Irresolution, Matthew Griffiths, London

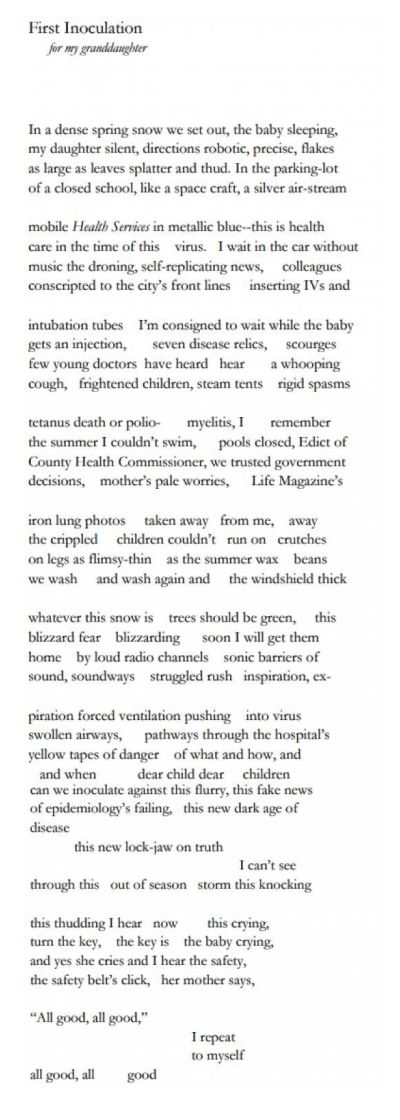

- First Inoculation, Owen Lewis, New York

- Driving in the Dark, Paul McMahon, Clonakilty, Co. Cork

- Nature Table, Robert Walton, Bristol

- Pouch, Sharon Black, Gardoussel, France

- Wimbledon 2020, Vanessa Lampert, Wallingford, Oxfordshire

- Washing Dishes: Reading Anna Akhmatova, Yvonne Blomer,Victoria, British Columbia

2020 Judges’ Reports

Mona Arshi writes…

It’s been an immense privilege to judge the Troubadour International Poetry Prize. Winning (and commended poems) that flow from the Troubadour competition have a reputation for excellence and the first thing to say is that the quality of the poems that arrived were very high indeed. Judging poems in a pandemic feels different and the submissions that arrived were different. These are challenging times for so many of us and I encountered poems steeped in grief and loneliness as well as very moving careful poems witnessing towns and communities closing down as well as the very real effects of a virus overwhelming families.

What was also clear as often happens in the darkest times, is that poetry and the writing of it was answering a need and it felt an important time to be judging this prize. One other observation I would make is that lockdown was an opportunity to incubate poem-seeds and open the door to some really interesting themes. I noted how far these poems travelled in the imagination, three words I would use to summarise the themes are reverie, anxiety and compassion.

There were many poems in nearly all the traditional forms, Sestinas, Villanelles, Sonnets, Ghazals plus tautly-arranged prose poems rubbing alongside longer narrative poems.

In so far as the judging task is concerned, I always feel it’s important to be very open when judging a prize and have no expectations, a sense of hoping to be surprised. A poetry teacher once told me ‘like what’s best in the poem and not what’s best in poetry’, which I think is a really important directive for prize judging… I also felt that when I encounter a poem I still follow my nose or as Emily Dickinson says ‘feeling physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know it’s poetry’

The winning poems are poems that felt natural from the moment the poet instinctively steps into first line until he or she leaves the room of the poem at the end and to quote Stanley Kunitiz all these poems “have secrets that poet knows nothing about’. In other words these poems seemed curious about something and the poem was a tool for excavating or revealing a simple emotional truth.

The winning poem Entre-Deux-Mers, June is a sinuous and wise poem telling us a story of the nature of resilience in an active poem full of lush imagery of the world of gardens and ultimately is a poem about compassion — I intend to pin it on my wall.

Filter Queen, the second winner is a brilliant example of how a poem can travel a long way in a short time, I admired the poet’s ability to evoke place and time and capture with such clarity a memory of a childhood ‘miracle’.

Calf the third winner is also an accomplished poem that travels deftly from a pasture to glaciers, it’s a beguiling poem in three large end-stopped verses which leaps from the concrete to the abstract and lands unexpectedly into some ancient but familiar land.

I want to say something about the commended poems as these were also very fine examples of poems that I hope are celebrated too. A sestina written by Maia Elsner Born in the year of the boar and its mixture of symbolism and rituals was a poem that not only keeps the ear alive but whose images become seared onto your mind. The Reed Flute and I by Abeer Ameer is a truly magical poem a pleasure to read and turns language into music.

As with all great poems these poems reward re-reading; which is the ultimate test for poems I think; how you are enriched further when you return, how the images proliferate, the desire to cycle back to the lines again.

Mark Doty writes…

Here’s a scene from an action movie: in a small, sealed room, water begins to pour from a pipe near the ceiling. Our heroes search for an exit and find none. The flood rises quickly to their ankles, then their knees and hips. Soon there will be just an inch or two of air near the ceiling…

Dramatic as it may sound, there were times my stint as a Troubadour judge felt alarmingly like this, though what poured into my small New York City apartment were poems. Thousands of poems. I’m not following in the footsteps of my country’s soon-to-be-gone President, whose first act in office was to lie about the size of the crowd at his inauguration. As a working poet and teacher, I read both for pleasure and for a living, and I’d guess I read in the neighborhood of 1,000 poems a year. I read this towering wave of contest entries in a matter of weeks.

And here’s the paradox: when I wasn’t drowning, it was wonderful. My days were flooded with poetry, an art I love and steer by. Thousands of distinctly individual persons had inscribed on these pages something of themselves at this moment: what they loved or feared, what they’d lost or longed for. Should some scholar find this trove 5,000 years from now, it would be a digital version of the clay tablets of Babylon, but concerned less with commerce, and not from any single city — a record of human interiority from poets writing in English around the globe. I would note, if I were that scholar, how deeply these poems were shadowed by fear, both of mounting crisis in the natural world and its immediate result, a global pandemic of unthinkable proportions.

And I’d be struck by the strengths that arise in the face of such a crisis of being. The intense love these poems embody for children and parents, lovers and friends, landscapes and animals, all that is vulnerable to loss. The will to preserve, in language commensurate with what matters. Unrelenting grief and the gift of good humor.

How on earth does one judge such a flood? I looked first for a sense of authority right from a poem’s opening lines, something communicated both by tone and the formal confidence with which words are placed on the page. I look for language that feels energetic, unburdened by received phrases. Perhaps most of all I want to feel that the poet is genuinely trying to figure something out, to think and feel a way toward insight. Good poems don’t just recite what you already know; they struggle to articulate a condition, to find a perspective, naming something of what it is to be alive.

And of course I relied on the discernment and keen vision of my fellow judge, to help me see what I might have missed while I was gasping for air. I know we made a better list together than I could have done on my own, and I’m pleased to celebrate the stellar poems we’ve chosen.

2020’s Winning Poems

First Prize, £2,000

Entre-Deux-Mers, June

Every rangy sidewalk-crack

hollyhock in Bordeaux

says the same damned thing.

Depend on nothing. Nothing

to shore you up, nothing to nourish

or validate, nothing.

They rise up against half the doorways

in town, coming out

of nowhere, staying

local, dressed up anyway,

posing before the stone

walls like florid hookers;

six feet tall or more,

veins displayed, stems

clad in starry hairs,

flexed petals powdered

with pollen as if to make

a point of how privation

shouldn’t stop you. They say

to stand your ground and take it.

Take neglect and turn it

to your advantage, build

a little empire of your own with it.

Turn it to pith and pigment, frill

and flush, flashy colors that look

ridiculously expensive, topaz

and jet, cochineal, Tyrian purple; turn

it to wantonly arrogant

dry fruits not in the business

of attracting anything

because screw that; take

nothing, owe nothing, come out

on top, present your proof

of concept ahead of schedule

and under budget: live on your own

terms like that and there’s nothing

anyone can do, though they will want to,

because once you need nothing

you will scare people, you will

make them want to cut you,

but here’s the thing–being hollow

doesn’t really make you stronger

but it does make you harder

to bend, and a structure

built on nothing

is near impossible to bring down.

Amy Glynn

__________________________________

Second Prize, £1000

Filter Queen

Later, of course, I won’t believe it.

That what’s scattered can be gathered back.

Saved from the swirling eddies of time and decay.

But now? Now mom opens the door

and shows him in. A heavy man wearing

a red-brown suit. Head sweaty as she brings

him water while her children watch,

certain he would not have faced the heat

without good news. Without the miracle:

he takes it from its case and turns it on.

Pours dirt onto my grandma’s rug, then waves

his wand and takes the dirt back up, changing

the rug’s dull blue to something I did not

know blue could be. From cold dishwater

to a pool of flame. He takes my father’s hand

and prints a scarlet O of suction in the skin.

I stare, astonished. Nothing has entered

my life like this. Even an hour later I’ll

know better. But for now? Now I believe.

Now dad’s signing a check, proving that those

in charge believe the war on chaos might

be won. The faint smudge of our lives preserved,

atom by atom. The world’s frayed loveliness.

Now nothing will fade. Mom is alive. One sister’s

humming something by Anne Murray, while

the other’s playing with two Lipizzaner horses,

which—my god, I had forgotten—she collected.

I remember staring at a row of them

up on her top shelf, thinking, not in words,

Be gentle, Time. Have mercy, Winds. Squinting

through dust-laced air. Seeing their gold hair gleam.

Michael Lavers

__________________________________

Third Prize, £500

Calf

On the far side of the hedge that bounds the churchyard

a cow lifts her throat to the sky and softly lows

— Mugit —

while, careful with straps, the men are easing the coffin

down into the pit they’ve dug deep against the difficulty

of driving rain. The sheerness of the pit’s sides

are threatened by the water. Lumps

break off. Fall in. Mugit.

Mugivit. Mugiebat. She lowed.

She was lowing.

Beyond — can you hear it? — the white roar

as the great glacier is unplugged

from her calf. The grief-struck cow

is lowing. Her orphaned calf,

helplessly removed and drifting, calls out

as she floats off into the unnamed bay

leaving the raw cliff of her mother.

Mugiverunt — what Virgil’s cattle did

when their quick calves were taken.

The cows and their calves bellowed.

Ancient words from a dead language,

spoken centuries before you and me

or lives like ours were dreamed of.

They understand by standing under

this severing present — their lament a cantus firmus,

to hold this shocked, irregular grief

in a compassion that’s simply having known

a pain like this so long ago. If I scoop deep

enough I might touch it, this sustenance

in old ground.

Elizabeth Cook

__________________________________

2020’s Commended poems:

__________________________________

The Reed Flute and I

after Mawlana Jalaluddin Rumi

As the reed flute sings you weep your sorrow;

your heart still beats in the place you left. The weight

of your yesterdays that were once tomorrows

halves you, just like the day the reed was cut

pulled from its bed, carved to carry the breath

of the carver to ears held far. Its inhale

is your exhale; as if straight from your own chest.

Its wails redden your eyes. Its larynx speaks your exile.

The same parting that split the reed from its bed

brings you together and you can’t know until

you’ve always known; when they said farewell, you bled

so long, knowing you would not fare well, and still

only long for the place your heart comes from.

Reading in tongues; all music yearns for home.

Abeer Ameer

__________________________________

Drag

A resting place, a cardboard, glittered room

to placate the avenging personalities, for whom

personality is a labouring duty. To fight

in a world that one is yet to embody,

fatal, fantastical or neither, simply void.

The nights are a means to pass the time;

to dress, undress, or redress a head of pearls,

a black heeled boot, lips in which to kiss the air,

as it embracingly applauds a song

that’s sung only as intent, not words, but

the abstraction of why words are all we have,

relentlessly pursuing the idea behind the form.

There is no way out of this life, only transformation

like all states of energy which remain untamed,

craft inaugurating craft, an endless task.

Though beauty requires a discipline of sorts,

be it life, or will, indebted to survival’s chance.

Now nonchalantly the singers take their place.

A curtain rises, ensuing that another falls,

like moon & sun; but in-between, made-up faces

reduce the world to blue – & kingdom come.

Alex Matraxia

__________________________________

In the Maternity Wing

When she stood to circle and reverse

(belly, distended; greyhound-legs, bird-lean),

tamping her bed-straw with little prancing steps,

he’d fetch the heat-lamp from its shelf, unspool its lead

to a cup-hook fixed to the ceiling of the shed.

He’d wrap it twice, leaning back to fathom

the perfect dangling length above her bed.

There it hung – infrared God-head to a kingdom

of smells – cigarette smoke over dank straw,

fetor of fungusy mould, stale dog-hair,

faintly stewing urine. He’d pad to and fro,

and, towards bedtime, station himself on an old chair.

From the yard, a chink in the door would show

him in two halves – knees and wellingtoned feet

warm and pink in the lamp’s heavenly glow,

head and shoulders, blue, in the limbo outside its reach.

Strange that it was taken as read back then

that he and my brother would be doctor and midwife

(when wives’ labour was out of bounds for men),

but between them they’d share the gravid night –

one of them there for when her panting worsened,

for the wrench-back of her neck and howl

at the out-spurt of each slick, sheathed bundle.

By the time we women of the house came down,

there’d be a line of wriggling pups

and she (wary now) would settle each one in,

after we handled it, with a quick jab and a rub

of her nose. But do I imagine that, later, he’d bring

a salty rasher-rind or a strip of fat ham?

That she – more docile than a daughter – would turn,

raise just her head to scoop it from his palm

with one loop of her tongue?

Ann Leahy

__________________________________

Anchorite

Snail glides, self-contained on her shining path.

Not for her some stone-walled enclosure but

as part of her slow, deliberate self,

wears a helical cell, made-to-measure.

Eyes aloft, she’s off on another pilgrimage

and mindful of every leaf of grass.

From time to time she’ll pause for reflection,

retreat, immured in her nacreous shell.

Who hears her prayers or can guess her visions?

Safe green shade at the foot of a hedge or

damp night’s coupling with brother or sister,

(each snail can be the one or the other)

Hermit life is the habit of her kind,

nomad member of a silent order.

Christine Macfarlane

__________________________________

Red Peppers

Your kiss reminds me

of the red peppers they serve

at the Budapest Cafe

of a red vinyl raincoat

one button undone

a splash

of rain getting inside

the glossy cover

of the child’s new book

the jukebox that wants

its music played

the first snow in December

silence everywhere

so much about to happen

David Tucker

__________________________________

Distance Runner

It is May or April, I lost track. Buses

run mostly empty. The bee-loud cars are scarce.

Men draw their toddlers to the edge of the pavement,

the old raise collars, pull scarves across their faces.

I sidestep dog walkers and their leads.

An empty police-car flashes at the park

gates. I run past a mother leaning towards

her child who is running towards her arms

as seagulls settle the unplayed pitches,

note the shoal-like evasions of families

detour through low trees where spiring flies

dangle bristly legs. I press index finger

tightly to nose in the hush-hush gesture:

snot-rocket followed by spit-bomb, strings

extenuate between lip and lap. I

contain billions, spiked contradictions.

A thrush under my feet could have been a leaf, but

I decide it was a thrush. Thought is law.

A man with five carrier bags lifts a can of

Special Brew; I circuit the park and he’s not

moved. With twilight mist lifts like tissue-wrap.

Distant headlights throw my wedge of shadow:

then the mist is over my head, is cloud.

Past the abandoned golf-course, the tow-path.

Low-flying geese ripple the water, their feathers

swash. The swans make quibbly wine-tasting noises.

Coots squabble into the night, tired party-goers.

On the bridge I move over the city

my ephemeral eye: underlit clouds,

the light-built trees. Unsettlement upon

the treacly surface skits and scatters, light

the consistency of spit or spirit.

Lights flash in the stairwell of the locked hotel

as, returning, under the moon’s new weight

silent ambulances ply from street to street.

Giles Goodland

__________________________________

Curfew

I.

The war began on a school day.

I saw men walked around

with faces eclipsed in rage and grief.

The moon was fatigued

by its tawaf around earth.

II.

The scar on this forehead is a sign of reincarnation.

She told stories to distract us from the dying voices.

My Mama’s eye was a theatre, for men

that praised the rusty edge of a blade

as they would a gate

that leads to a garden of proteas.

III.

Wrinkles sprouted from the side of her eyes

after the new millennium, boys my age died in sleep.

On the sky that day were the stripes

of all ninety-nine shades of red.

We walked streets during the curfew

in search of florets,

and for the first time in weeks,

I said a song in praise of my lunch box.

IV.

We have all lost something, and in their memories,

we held congregation in a market square.

In a history that may go undocumented,

our scars flickered, as if caressed

by the yellow hands of a sleeping God.

Hussain Ahmed

__________________________________

Secret Baptism

It wasn’t that we were afraid for his soul.

At a child’s birth, you get a long look at

nakedness. You can grasp how very tender

we are. But my God, his birth. The terror

of it. The bleep of the fetal monitor. His

neck, craned red to breaking. Rage-soaked

corpuscles, a swollen creek, spilling our

DNA secrets. Fingers, thin and alien, in

search of some fleshy five-prong socket.

The small shocks bolting across molecular

raiment. Baby skin. A holy garment.

The seeding, the wait, the doubt, terror.

And then, the intoxication. That by this life,

this life occurred. So, yes. We took the baby to

the lake in town. Skimmed its October-sullen,

green-gray water into the sieve of a hand,

to wet his unsullied forehead. Unable to

pick a religion, we blessed him ourselves.

I know. But you’ve wanted to have something

both ways, surely. I said, In the name of the

Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, in the

charcoal tongue of my mother, burning with

all she found sacred, its incense of losses.

And what would have happened if not? Our

acts, still rippling. We cannot know now.

Intent, a switch we flip in dimly lit hours,

precedes so much of what we stumble upon—

the right temperature of soup as it simmers

on the stovetop, the smell of planted jasmine,

the buzz of a wasp outside a repaired window

screen, all that is safely inside or out, the sound

of his tiny heart. My God, the sound of his tiny

heart. And the simple impulse to grow it.

Jessica Cohn

__________________________________

The Tees Roll

This was a flashy river. After a storm,

the shallow stubborn bedrock

beneath the gathering grounds

forced the river to take rainfall

all at once; then, unannounced

and unpredictable, the great Tees Roll

went barrelling down. A yellow wall;

another river, riding bareback

on the first; like the shovel of a great digger

ploughing branches and boughs,

and the bodies of feckless yows

before it. Sometimes it took out bridges,

sometimes men. Corpses rode the wave,

carried downstream as far as Blackwell.

The landlord of the High Force Hotel

would telephone to Middleton;

Stop the cars and close your bridge

we’ve got a roll coming down.

Some remember the warning sound

of the dangerous river, singing.

Once, a whole wartime platoon

of lowland men was washed away

with their pontoon bridge, at Barney.

Tamed by reservoirs, the old Roll

is history, but wary anglers, wading out,

still push a twig into the bank

to mark the level. In angry spate

even now, a flood will rise from nothing,

calling out warnings from monitoring stations

of hundreds of Cumecs passing.

Judi Sutherland

__________________________________

Mouth Game

after Vasko Popa

Someone be the mouth.

Someone else be the stomach.

The one who is the stomach speaks the truth.

The one who is the mouth must not.

The mouth must speak only

in polysyllables, let them clatter together

like dentures, like a rope of empty oysters.

The louder the mouth can shout, the better.

The language of the stomach is thunder,

which must argue from far away, and always

reach the bystanders second. This cannot be played

without bystanders, and does not stop

till the game with the stomach

is forgotten, and all the bystanders

have assumed the role of mouths.

Katie Hale

__________________________________

Born in the year of the boar

To begin breath in the year of the wild boar

is to be wise, my mother tells me & later I learn

that aside from humans, pigs are the only

animal to go out purposefully to get drunk.

Father tells me of Vishnu diving into the sea

to rescue Bhu Devi, Earth goddess, who creates

a world for all of us to imagine & create

our own creation myths: Vishnu as a wild boar –

there are many avatars, walking across the sea,

Jesus, & Buddha also, representations. I learn

some choose to incorporate, not reject, the drunk

evening taking in the smells of bird-eye chilies only

from Tesco’s, argument between two lovers, only

wanting & grabbing skin, the whispers created

in dilated eyes, the sparkling girls, long drunk

on beer cans. Booze, the first commodity, the boar

people took when lockdown was announced. We learned

what society could not live without & the sea

crashed against the shore, uncaring. The sea

holds its own violence in check, takes & takes only

to release foam bubbles, breath. I learn

deep breathing, counting one-to-nine, creating

stillness or trying to. I think of wild boars

running free in buttercup meadows, our drunk

moments. I dream of dancing, of holding you, drunk

on touching & closeness. Of falling to the sea

bottom & breathing deep, of Vishnu as giant boar

among coral reeds & fish, drawing out only

what does not belong to ocean. My sister creates

a paper swan to float as long as paper lasts. I learn

to cry at petals falling & fallen fireflies. I learn

that letting go is never easy. I ask but the drunk

artist on the corner provides no answer as he creates

an echo of constellations. There will always be sea

rising, fragile cry of gulls as waves break only

promises of safety & drown coarse cry of wild boar

as it creates a nest for its young, learns the bitterness

of bark. & the boar-cubs carve a statue to the drunk

sea, its waves collapsing, only a massacre of spume.

Maia Elsner

__________________________________

On Reading Olav Hauge

I’m looking through the poems again

for some thread back to the path – not even the path

I lost – any path, the silver one the boat took,

the one up through a birch wood to the waterfall.

Looking back and forth between the languages,

trying to imagine this poor apple farmer

from the west of Norway in an asylum

(like John Clare) or addressing a poem to Li Po.

He tells us Don’t Come To Me with the Entire Truth

(tell it slant?). Looking back and forth between

the facing pages, one language, then the other,

in his vast world crossed too by dung-beetles and rocs –

when a word locates me very precisely on

a speck of an island one degree south of the Arctic Circle,

where a click of knitting-needles falls

regular as breath. Three eiders are nesting across

the narrow sound. A skua bides his moment on

a rock near. I look up from a book about the island,

and ask what does méd mean? Bearings,

says my friend, how a boat finds its fishing-grounds.

Margaret Wilmot

__________________________________

Mark Chamberlain

__________________________________

Crown Shyness

…a phenomenon observed in some tree species, in which the crowns of fully stocked trees do not touch each other, forming channel-like gaps. –– Wikipedia

If you want to see the pattern that they’ve made

you need to look up from the forest floor

in summer. Ends of branches don’t abrade

each other, but leave ripples in their shade,

as if they’ve grown wary of that war

that moves inside the pattern that they’ve made.

Mapping the movements of the winds that flayed

and thrashed their heads till they became heart sore,

they made room for whatever might abrade.

It took time. Now the channels are inlaid

and every shivering tip has taken score,

moving in time with the pattern that they’ve made.

Seams in the brainy dark, a bright cascade,

a shyness almost human at its core,

a canopy of gaps that can’t abrade;

no matter how many arguments have swayed

the trees, the wood –– the gap between the door

and frame inscribes the pattern we have made,

that only stillness and silence will abrade.

Mark Granier

__________________________________

Irresolution

It’s called the future, and it begins

And begins, but no longer has you in.

I have started but mis-stepped: I say again

Now is the future that we’ve all talked up

And this one is but isn’t. A future and,

A future or, an always rising, always filling cup;

The grid space of a map becoming land

We walk out like a queered pitch in a blind-

Man’s buff — a door that taken at its height

Opens left, but at its depth swings right.

I clasp my skull, which is filling with two minds.

A step back must be kicked on by the keeper,

Kept in play. Let’s not start all this again.

I’ll take a lie-down. We are so many sleepers.

Matthew Griffiths

__________________________________

Owen Lewis

__________________________________

Driving in the Dark

We were driving along a country road

under a night sky when a bird slammed

the windscreen – I didn’t see it, neither

of us did, we just heard the thud of it

rebounding off the glass and I looked back

at the empty rear seat and saw the image

of our unborn sitting there grinning at

a punchline only womb-kind hear.

The image stayed there for a moment,

a flickering light in the half light

of what I feared had risen up from

a shadow play between what I had held

underwater for too long and what my own

shadow had twisted its long neck into –

I said nothing but when the mirage

faded out into the faded upholstery

I turned back to the darkened sky

of belly under which she was sleeping,

fastened in by her mother’s seatbelt

then took out the ultrasound scan

I refused to look at in the hospital

and saw her, first time, curled up

in the womb-dark cave as hollow,

dark and deep as the night sky

under which we were driving —

like the bird who didn’t see us coming,

or know into what it was flying,

yet was still eager to get there.

Paul McMahon

__________________________________

Nature Table

Under the wall-display of sunflowers and daisies

splattered like star clusters on a sugar-paper

sky, the table sat at the back of the classroom

displaying relics we’d gathered in woods and fields.

Chunk of stone, its crystal facets glinting

secrets. Garland of glossy seagull quills.

Clutch of hazelnuts in their fuzzy husks.

Dessicated leaves of beech, ash, elm

and sycamore we’d copy in our drawing-books.

From an era with so many noughts on the end

our mouths hung open – an ammonite

like a foetus sleeping in Jurassic dreams.

When Mrs Jones showed us a spray of acorns

in their cups and told of Prince Owain rousing

his troops at Pontfadog, we cheered, ‘Ymlaen!’.

The day she ran her finger along a sprig

of rosemary and spoke of remembrance, a fragrance

filled the room and we sighed, sad as willows.

And once, when Michael brought a blackbird’s egg

he’d found by a hedge, she let me lift it to my eye

to peer into the hole he’d blown. It felt so light,

I thought I held a bubble of air and all

I could see was the white inner wall of a blue-green world

nestling in my hand, perfect, ready to open.

Robert Walton

__________________________________

Pouch

Every day, I slip this drawstring

pouch of eggs

inside my dress,

cosy them against my breasts,

hold them warm while

I sweep the flagstones,

milk the goats, feed the chickens and the mule,

make bread and daube and boudin noir,

my own blood

coaxing them to life.

One year there were so many,

I took to bed for fifteen days

like a fifi in her nesting box –

knitting, crocheting,

reading God’s word, turning

most carefully beneath the eiderdown

to protect my fragile cargo

while my own sons laboured

on the land,

my daughters at the mill.

Bertran’s preparing the magnanerie:

mending trays and ladders,

weaving us new baskets. Soon

the fires will be lit,

the mulberry leaves laid,

the silkworms hungry

and we’ll go about our chores

to their background hum, to the stench

of shit and wilting vegetation,

dust rising to the roof, light pouring

through the narrow windows,

those tiny lives that hatched against my heartbeat

fattening beneath sprigs of broom

dotted with their white cocoons

like moons ensnared in branches.

Sharon Black

* fifi (Fr.) – a bantam hen known for its strong brooding instinct

__________________________________

Wimbledon 2020

I’m changing what happened.

In the new truth my dad did not die young.

He’s out on the street in front of his house

with his old man’s face lifted to a sky

that’s cloudless, brilliant with summer.

A purple hot air balloon floats high over the city

he chose for its famous bridge

and a woman who loved him for a while.

He’s standing to watch the balloon drift,

waiting for the roar and the orange blast of fire.

He says science and magic don’t fall out.

They just stay with what they know.

Years ago he fixed a hole in his garage roof.

All afternoon a blackbird flitted and sang

a song that pleaded for mercy

because she had built her nest

in a dry building with a skylight,

that was now a prison with her chicks inside.

So my dad climbed back up his ladder

with a hammer and gave that bird a brand new door

to the sky. Now he walks slowly

to Clifton Village for ice cream. Really good,

bad ice cream with cookie dough

and caramel sauce pooled in the middle.

I’m on my way, driving south

on the road that leads to him.

We’ll watch the tennis and whichever man wins

my dad will cry, then go outside

and cut the grass. I’ll stand at the window

to see him smile to himself, because he witnessed

another man’s dreams come true,

and he saw that man kiss a shining trophy in the sun

then raise it to show the sky.

My dad will put the lawnmower away

in a garage with a leaky roof

and come back in. He’ll give me a spoon

to go first and we’ll eat ice cream

straight from the tub, because my dad

knows how to take a victory and make it

his victory, and my victory.

Then all weekend heaven will be real.

Vanessa Lampert

__________________________________

Washing Dishes: Reading Anna Akhmatova

Sometimes, hands in warm water, I am Eastern European. Sometimes Jewish, eating potatoes and warm borscht with friends from New York. Their accents: I want them in my mouth, shaping my palate and the taste of what I see on the street.

Have you considered a quiet revolution or a hunger strike?

I often ponder water in this Northern country, its freedoms fractured,

winter not its only crime.

We took a bus from Vilnius to the castle town Trakai. How language gets trapped in the lint of memory, in the slaughter of time. The Russians had rebuilt the crumbling citadel. No history in the aligned walls, the perfect bricks.

Are we like soldiers, frozen poplars in a vice?*

The blue metal sting of cold. I feel

Russian, plunging my hands into the metal sink,

human, by which I mean, ready to flee.

What is it to wash dishes? To live alone in writing?

Under the sink, a mouse nibbles at crumbs and runs from what it hears. Its small hands are mine, lifted claw-like and white from water. Somewhere the mouse will find a soft place.

What is longing? Warm hands softened by lamplight

Yvonne Blomer

*from Akhmatova’s poems ‘For Osip Mandelstam’