Troubadour International Poetry Prize 2018

Winners

The following prizewinning poems were chosen by our 2018 judges, Jo Shapcott & Daljit Nagra, & read by winning poets at our Troubadour prize-giving on Monday 26th November 2018:

- First Prize, £2,000, What My Net Dragged to the Surface, Cuifen Chen, Singapore

- Second Prize, £1000, ‘there’s rue for you; and here’s some for me’, Doreen Gurrey, York

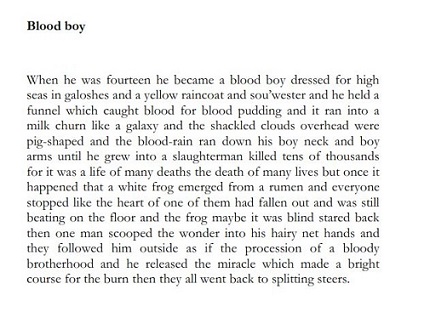

- Third Prize, a week-long Arvon writing course, Blood Boy, Meredi Ortega, Aberdeen

& with thanks to 2018 prize sponsorship from leading poetry magazines & poetry publishers,

Five prizes of one-year magazine subscriptions from:

- New Ohio Review: Immigrant Song, Chris Greenhalgh, Milan, Italy

- MsLexia: Ophelia’s, Like, Response to Hamlet, Tracy Youngblom, Coon Rapids, USA

- Poetry Wales: I Stepped into my Father’s Shoes, Paul McMahon, Belfast

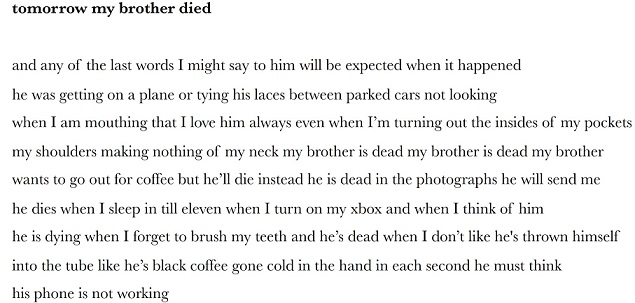

- PN Review: Tomorrow My Brother Died, William Griggs, London

- Under the Radar: In the Dog Kitchen, Ann Leahy, Dublin

Five prizes of book-bundles each with 6 latest poetry titles from:

- Bloodaxe Books: 7 Ways of Being More Tiger, Hilary Watson, Cardiff

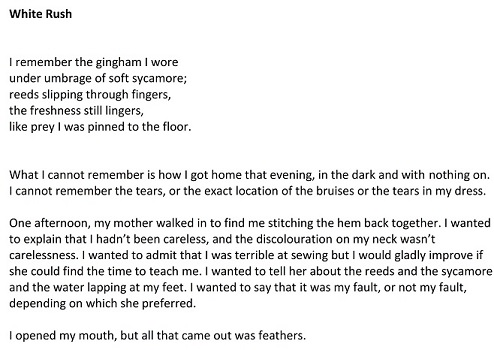

- Seren Books: White Rush, Kristal Phillips, Kenilworth

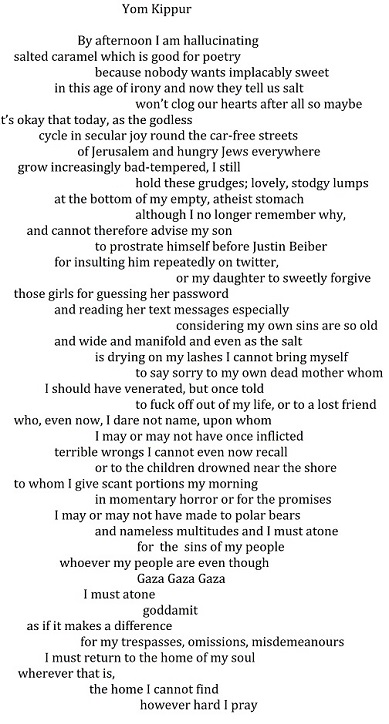

- Carcanet: Yom Kippur, Jacqueline Saphra, London

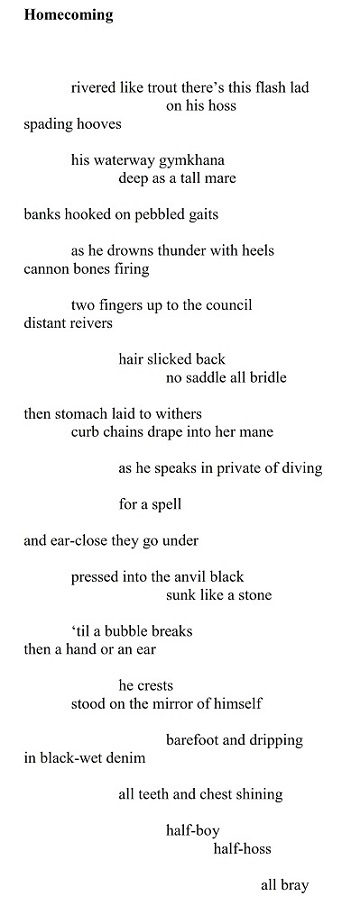

- Faber: Homecoming, Jo Clement, North Shields

- Nine Arches Press: The Days, Vanessa Lampert, Wallingford

Longlist

The poets whose work the judges chose in their longlist were: Alice B Fogel, Andrew Hamilton, Ann Kaiser, Anne Macaulay, Asma Mani, Caroline Maldonado, Charlotte Baldwin, Christopher James, Claire Collison, Claudia Daventry, David Olsen, Edwina Gleeson, Elisabeth Sennitt Clough, Elizabeth Barrett, Eric Berlin, Erin Halliday, Gregory Warren Wilson, Harris Brine, Helen Overell, Howard Wright, Ian House, Jayne Stanton, Jim Garber, John Gohorry, Jonathan Mendaoz, Julia Webb, Julian Stannard, Karen Green, Karen Kovacik, Keith Jarrett, Leonardo Boix, Linda Cooper, Lindsey Holland, Louisa Archer, Lesley Saunders, Lucy Cage, Lucy Hamilton, Lucy Watt, ME Muir, Majella Kelly, Mara Adamitz Scrupe, Mark Anderson, Miriam Calleja, Mirkka Jokelainen, Nancy Klepsch, Neil Young, Niall Bourke, Nick Norwood, Olivia Stewart Liberty, Pamela Johnson, Pam Thompson, Paula Finn, Polly Atkin, Ricky Ray, Robbie Frazer, Robert Stein, Royston Tester, Ruth Aylett, Ruth McIlroy, Samantha Wynne-Rhydderch, Sarah Westcott, Seth Canner, Simon Rees-Roberts, Supriya Kaur Dhaliwal, Thomas Malloch, Tim Waller, Tista Austin, Warren Czapa, Wendy French, Wendy Pratt & Wes Lee

2019 Judges’ Reports

Jo Shapcott writes…

It was a privilege to be given a glimpse, via the great pile of poems in this year’s Troubadour International Poetry Prize, of poets’ concerns during this moment of change and uncertainty in the public sphere. I was expecting sheaves of poems about Brexit, but strangely there were only a few. Relationships, and how to chart them, were on writers’ minds; the ecological disaster that we have brought on ourselves; women’s stories and experiences; and a prevailing general sense of unease – like a beat before something ahead that we can only just sense. But as the best poems rose through the pile, I was not at all uneasy about this crop of writers’ sense of what a poem is and might be. We saw boldness and innovation, frank emotion where it was needed, formal skill and intense musical and visual sensibility deployed just so. We think the final batch makes a great anthology in itself, quite outside the placings of the individual poems. We are proud of all the winners here and commend them to you here.

winners of the 10 poetry-publisher & poetry-magazine sponsored prizes:

The Days, by Vanessa Lampert: The Days attracted my eye and ear for its gentle interrogation of memory, of nostalgia. The past, made up of those shining, inhabited days and open innocent faces, is gorgeous but threaded through with a whiff of trouble. The sensual world of the poem is heavenly but smudged, dirtied up a little in a nod and tremble towards the future.

Immigrant Song, by Chris Greenhalgh: the narrator of this powerful poem becomes the point of convergence for lines of internal and external emotion in the between-world of airport immigration. Surreal, even ecstatic imagery provokes resonances of sacrifice interspersed with moments of high comedy which leap out of the always-strangeness of the mundane.

Ophelia’s, Like, Response to Hamlet, by Tracy Youngblom: this poem is, like, Awesome. It’s a skilful and fun riff on Hamlet which revels in an almost Shakespearian dive into our contemporary vernacular. You wouldn’t want to cross this Ophelia, particularly on Instagram, although her vulnerabilities cross the centuries.

Yom Kippur, by Jacqueline Saphra: a finely-tuned, witty and utterly contemporary meditation on atonement. The poet uses a single long, beautifully-wielded sentence which winds through the poem, pushing against the line endings to create the friction which drives and reflects the narrator’s internal conflicts.

In the Dog Kitchen, by Ann Leahy: this rich and warm poem is full of the sound of meat slapping and cleavers thwacking, the whole dog kitchen orchestra fully engaged. A nicely handled rhyme scheme in quatrains draws the poem together, a counterpoint to its overall music.

White Rush, by Kristal Phillips: the form of this poem brought to mind the Japanese Haibun with a strong formal turn between the rhymed part and and the prose poem, and a parallel turn between the terrible event described and its aftermath. The poem’s stillness, beauty and measured tone all work together to both belie and foreground the physical and psychological cost of the attack.

I Stepped into my Father’s Shoes, by Paul McMahon: I admire the dark atmosphere of this poem, how the writer has crafted its sustained sense of dread alongside the astutely observed details of the scene which are indelible in the father’s memory. Most of all, the poem embodies the circularity of violence. The power (and terror) of empathy and of poetry, are here, too, as the trauma is repeated, re-enacted through the writing and reading of it.

7 Ways of Being More Tiger, by Hilary Watson: yes, I’m sold. I’d like to be more tiger. Witty, fun but always truthful, the poem brings to life our internal, helpless everyday emotions and directs them through tigerishness towards a roaring resolution. The plain, direct language enhances the push and pull of the poem, its drama and comedy.

tomorrow my brother died, by William Griggs. This is a poem which miraculously makes you feel time, as if it were an emotion in itself. The very idea of the death central to the poem is so overwhelming that it doesn’t matter whether is has just happened, is happening now, or is about to happen – the emotional reality is all the same.

Homecoming, by Jo Clement: his poem brings to life its young subject – ‘half hoss/half boy’ so vividly he leaps of the page in his ‘black-wet denim’. While the poem is cinematic in its strong vision of boy and horse, it is also rich in language – a colloquial, almost private language – for the particular communication of these two.

Third Prize:

Blood boy, by Meredi Ortega: there’s a rush of feeling and passion in this prose poem, all one sentence, breathless with itself, telling its own important fable in one outpouring, telling a history which runs from the teenager taught to deal with animal blood and then graduating into mass-slaughter. There is a moment, a beat within the poem and its story, when one life is saved and when change seems possible, but the rush to killing resumes. The casualness of the blood-letting in the poem makes its own powerful case for its opposite: the physical detail and sheer gore which are mostly hidden from day-to-day life are made vivid through this skilfully charged work.

Second Prize

‘there’s rue for you; and here’s some for me’, by Doreen Gurrey: seven haikus set out as paused stanzas, Seven flowers or flower thoughts. Seven moments in a story of abuse. This combination of elements works together to give us a fine lyric narrative in which the overlying flower story allows the horrifying truths of the narrator’s experience to unfold. The innocence embedded in the floral imagery is shockingly betrayed and the stillness nevertheless achieved in the poem allows a larger horror outside its words to emerge. It is a subtle poem of devastating sweetness, skilfully made, with proper outrage at its heart.

First Prize

What My Net Dragged to the Surface, by Cuifen Chen: with its echoes of The Tempest, here’s a poem which drags a wonder of detritus, actual and psychological, from the deeps. The poet’s net draws up the wreckage of a relationship as well as tide-wrack objects: a chipped cup, pebbles, a leaf, all of which resonate beyond themselves. But bones are the main treasure, and their meaning, too, is as layered and multiple as a deep-sea bed – a graveyard, a cathedral, the poem itself. The poet carefully unfolds the net to reveal a skilful emotional structuring, made to look like a disordered heap of this and that, but with items and layers forensically selected as the poem moves down the page, gathering in a momentum of feeling.

Daljit Nagra writes…

When I’m reading a good poem, a poem that has me gripped, I often feel as though I’m surfing on one of those wonderfully long solos by Jimi Hendrix, where he can sustain memorable phrasing and go beyond the expected length with a series of unexpected turns. Perhaps a song such as All Along the Watchtower with its building lead solo and extension is what I look for in a good poem, a poem that embarks on a journey that continues moving outwards before it takes a turn homewards.

A good poem could also be imagined in terms of pneuma. The Greek term for breath, which in Greek medical terminology denotes the entire air needed to sustain the body at a given moment. Or seen in different focus, pneuma is the entire breath needed at each interval to sustain consciousness. Given that a poem is a record of consciousness in time, a poem is a form of pneuma. A poem’s pneuma, from start to end, is the sustained breath of a poetic vision. When I read a good poem, I’m keen to feel the full weight of the poem’s breath in it’s distribution across the entirety of the poem. The one whole breath of consciousness animating the poem and keeping it alive. The poem comes to the end of its pneuma because the reader must inherit this pneuma, this breath of the poem and allow it to exist within themselves.

Judging the Troubadour International Poetry Competition was very much an action of reading poems that could go on a thrilling riff, that could extend the breath and broaden the consciousness of the poem. My favourite poems were those that seemed to have stayed inside me, and after repeated readings their musical journey, their pneuma had become my experience. So this is my somewhat strange way of explaining how I judged the competition to determine my favourite poems. In addition, I always enjoy working with my poetry hero, Jo Shapcott. I admire her calm thoughtfulness, her humour and her critical laser.

I loved What My Net Dragged to the Surface because it built on the original vision and kept extending the penuma of the poem, from environmental devastation and plunder to an exploration of the tensions between lovers. The poem seems to aspire to the condition of pure metaphor, both debris and relationship seem lifted into a field of symbolic tensions that can not be resolved. I loved the many curious images, the assured lineation and language which worked on several levels at once.

‘there’s rue for you; and here’s some for me’, is a powerful meditation where the near silent cadence of the whispering victim makes this series of elegant haikus a terrifying narrative of disclosure. The proper work of lyrical poetry is exquisitely built into the single coherence of the pneuma, with the deflowering being devastatingly enacted through scrutiny of flowers. These floral correlatives help quell the emotions so the artistry of the poem can shock all the harder.

Blood Boy is an energetically sustained prose poem that builds its pneuma around the mythic construction of a slaughter boy, the harsh realities so overwhelm the narrative that even a miraculous event is subservient to the daily grind. Have we lost the power to wonder, have we too gone far down the throes of death, or so the riffing of the poem seems to indicate.

2018’s Winning Poems

First Prize, £2,000

What My Net Dragged To The Surface

Bones of stingrays, bones of catfish,

and slippery, broken bones of eels were tossed

in a snarl of rope. I plucked out, assembled

bones of a seahorse, swept away by the current,

its tail still coiled

round dried-up kelp, clinging on

to a place it knows. Pressed in the mud,

I found bones of a leaf, torn from its branch

by a monsoon out of season. The skeleton veins

crumbled as I touched them, just like the leaf

you brushed from my hair on a brittle day.

There were pebbles: bones of the earth, knuckle-bones

that rattled a chorus of elegies

to the bones of a boat. The prow was curved

like a collarbone, splinters choking up its throat.

I spread my net on the shore, sifted through

bones of birds, bones of stray cats,

cigarette butts, crushed cans, a glass bottle

with a chip in its rim. You’d cut your lip

if you drank from it. You drank from it anyway.

Elbow-deep in the wreckage, I grit my teeth,

those little bones in my head,

digging up bones of a kite we unwound and lost.

The string in my palms was a twisted spine, its vertebrae

misaligned. The day it slipped from my grasp,

I ran after it. You watched me

from the riverbank. You had already let go.

We have been here before, you and I, drowning our

bones in the tide, making a memorial

of freshwater and ruins. I say

my net has dragged a graveyard to the surface. You say

I have unearthed a cathedral of us.

Cuifen Chen, Singapore

__________________________________

Second Prize, £1000

‘there’s rue for you; and here’s some for me’

(Hamlet Act IV, scene V)

1.

A shrinking violet

that’s what he called me sometimes

huddled in the porch.

2.

‘You are the first flower’

the priest said when I gave him

pansies from the park.

3.

Pensée, Mary’s flower,

who kept her thoughts to herself.

He touched me here, here.

4.

In the leaf litter,

Nightshade, black belladonna,

wide-eyed innocent.

5.

Passionflower wreathes

the wall, their inky crosses

have me in their sights.

6.

Where X marks the spot.

‘Put your hand here, now’ he said,

his mouth full of O’s.

7.

Lady’s Modesty,

violet, grows where shadows fall,

small, always looks down.

Doreen Gurrey

__________________________________

Third Prize, a week-long Arvon writing course

Meredi Ortega

__________________________________

Five prizes of one-year magazine subscriptions:

Immigrant Song

To enjoin trust, I remove my belt and shoes, placing my laptop

and toiletries in one tray, folding trousers and shirt in another.

To prove I’m above suspicion, I strip off my underwear and walk

naked through the arch like a messiah entering the gates of the city—

except the machine still buzzes. I spread my arms in a crucifix

the way stewards do when they glide down the aisle, clicking with their

fingertips the overhead lockers shut. And here’s the thing: slowly I

become conscious of contending odours from the perfume counters,

squares of chocolate tensely present under silver foil and beyond

plate glass the aircraft, their engines pleated like mushroom gills.

The hubbub of the concourse comes together inside my head. It’s at

this point I experience some thirty seconds of weightlessness.

The objects in my tray rise in tumultuous slow motion. I start to

levitate, still with my arms spread wide, aware of other passengers

halted in their queues looking up. It is a moment of perfect balance,

with two alternative endings attached — one where the assembled

throng strips off and an orgy ensues, which gingers the search

for meaning and ignites a feeling long and hot down to my knees,

and one where a security guard opens fire, my blood flung like

torn petals, staining the clothes of those below. I say my name over

and over as if rearranging my insides. People begin to sing.

Next to me, a fly unveils the church windows of its wings.

Chris Greenhalgh

__________________________________

Ophelia’s, Like, Response to Hamlet

Hello? I was, like, hiding, not deaf. I could hear you.

You were all, poor me, my calamity, blah blah.

Seriously, spare me your, like, torment.

Dude, really, you think too much,

and, you know, I had feelings? I mean,

I should have known if you couldn’t

make up your mind about your life—or whatever—

you couldn’t make up your mind about me.

You couldn’t see we’d be awesome together.

But I hoped. For a second I was like,

Bonus! This dude is totally into me. Then you said

you never sent those gifts. No way—

like, totally make me barf, I had them

in my hand, and you took them back,

so, OK. Maybe it’s not fair

to blame you for what I did, but, like,

you tricked me and then were all, like,

flirting at that play, and I was supposed to

act all cool and ladylike. Totally bogus.

Then, like, end of story, you totally

stabbed my dad. No way, more death,

you were, like, obsessed.

I shouldn’t have been that into you

in the first place. They all said

you just had a hard-on for me. Gross.

I didn’t believe it and I was, like,

totally stoked about your rad poems.

I couldn’t, like, forget you. As if.

It seemed way easier to repeat your

question and finally answer: to be or not to be?

Not.

Tracy Youngblom

__________________________________

I Stepped into my Father’s Shoes

the moment he stepped out from his off-licence doorway

onto the pavement and stood next to a lamp-post –

it was night time but the streetlight cast a yellow haze

over the area as gunman number-two stepped out

of a doorway three doors down and walked

towards my unarmed father while reaching

his right hand into the inside pocket of his coat —

but when he drew his hand back out it was empty.

The killer stood six feet away, my father said,

and the expression on his face was one of wonder –

as though gunman number-two thought he was a ghost

standing before him bathed in the yellow shimmer

of the streetlight. Gunman number-two was no amateur –

this was meant to be the tenth that he and gunman-

number-one were to add to their kill-list, so why

didn’t he take out his gun out and shoot the target?

But if we hold it there, and rewind a few moments,

to the beginning of this assassination attempt,

we will see my father trying to lock up for the night

as gunman number-one steps out of the darkness

and presses a Mauser pistol into my father’s chest,

then tries to force him back inside the off-licence

where he can shoot my father without being witnessed

but as gunman number-one steps forward

my father steps to the side, and, with his one

famous Ju-Jitsu move, The Flick and Spin,

the Mauser flies out onto the street

followed by un-gunned number-one,

who then gathers himself from the gutter

and runs up the street and around the corner.

And this is the moment, many years later,

the same age as my father was on that night,

that I step into my father’s shoes, and then step out

onto the pavement and stand next to the lamp-post.

It is night time but the streetlight casts a yellow haze

over the area

and the killer approaches.

Paul McMahon

__________________________________

William Griggs

__________________________________

In the Dog Kitchen

He’d slap down a giant beef-heart in a shed

out back, cleave it, neat and deft, or he’d hew

shreds with a thin blade from a boiled sheep’s head.

Beside him, a frothing, grey-brown stew

roiled on a two-ringed hob. (Oh, that fetid steam!).

In a cracked mixing bowl, he’d flex and spread

his fingers, sink them, pliant, knuckle-deep,

in a (soaked and spongy) loaf of stale-bread.

He’d alternate brusque commands (‘get out from under

my feet!’) with half-endearments (‘there’s the girl’)

to his old amanuensis, the pointer,

watching for the moment he might pick and hurl

a scrap (in one swift movement without turning).

In the end, she’d squirm to get ahead of him

out the door to where the rest waited, whining,

tails wagging, by their battered roasting-tins.

He might fling his shoulders back to draw

on a cigarette, or, in a different mood,

whistle some number from the jazz repertoire.

of his youth. No mother could have watched her brood

more approvingly as they tucked in. And did we

ever see him preside with more grace

than at this late-night ritual, this dingy

inversion of the day’s domestic embrace?

Ann Leahy

__________________________________

Five prizes of book-bundles each with 6 latest poetry titles:

7 Ways of Being More Tiger

I

A man pushes in front of you in Co-op.

You eat the man then ask the cashier

for Menthol Super Slims and change

for the bus.

II

There’s a puddle in the park

that your friend’s dog shows

a fondness for. Remove your coat.

Fold it. Take off your shoes,

tie the laces and fling them

at an impossibly high branch.

Having doffed all clothing

double-dress your friend.

If alone, dress the tree already sporting

a fabulous pair of brogues.

You’ll wade through the water,

realise it’s only ankle deep.

III

When the postwoman ignores the

No Shit Through the Door, Diolch

you put up yesterday, drench her face

with your claws, lest she forget

and repeats the mistake.

IV

Be kinder to pigeons. Really.

They are your lost childhood

reincarnate in pigeon-form.

V

Sleep. Belly-up

whenever

wherever

the sun

cares to shine.

VI

Poop discreetly.

VII

Ignore all written instructions henceforth.

You are not illiterate or dyslexic or slow.

You’re a fucking tiger. Deal with the thing.

Hilary Watson

__________________________________

Kristal Phillips

__________________________________

Jacqueline Saphra

__________________________________

Jo Clement

__________________________________

The Days

The days will not have all been summer.

Look how we think them backwards

fine-weather clad–move them home

with us in shorts and dresses–tether them

with knotted thread to take the weight of

all we might need later. The almost holy skin

of our children. The backlit blue of their eyes,

how we made them skipping, gorgeous.

We said you must not touch the billy-goat,

the oily stink of him, his sexed-up bleating–

then held the hatchling turkey chicks,

cupped their untroubled bodies to our faces,

whispering Christmas dinner. How bright

hope bloomed in the courtyard, picked out

the shapes in clouds. We have lived these days

a long time gone, everything–trees

and a soaring kind of freedom, honeyed

in expected birdsong. We stood up when we

saw that we had fallen and all the way home,

the stench of billy-goat clung to those who slept.

Vanessa Lampert

__________________________________