Troubadour International Poetry Prize 2021

The following prizewinning poems were chosen by our 2021 judges, Linda Gregerson & John McAuliffe, & announced at Troubadour International Poetry Prize Night Online on Mon 6 Dec 2021 (see judges’ reports & poems below).

- First Prize, £2,000, Balthazar, Sam Garvan, Cambridge

- Second Prize, £1000, Need to Know, Geraldine Mitchell, Louisburgh, Co. Mayo

- Third Prize, £500, The Course to Naming a Brook, Alun Hughes, Stroud, Glos.

Commended poems:

- Portraitist, Christina Lloyd, San Francisco

- A Shanked Cable, Andrew George, London

- What we take with us and what we leave, Mike Barlow, Lancaster, Lancs.

- A Table of Green Fields, Christopher Twigg, Talgarth, Powys

- When I Whatsapp you in San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Alexandra Corrin, Gosforth, Tyne and Wear

- Beluga, Gravesend, Sarah Westcott, Bexley, Kent

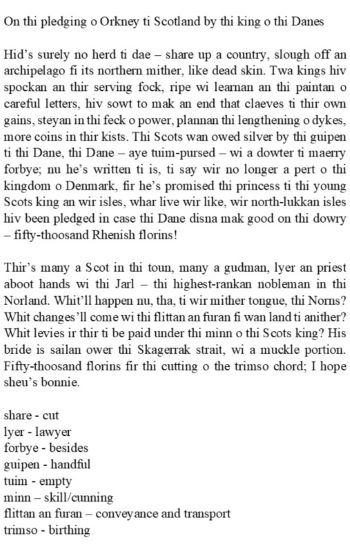

- On thi pledging o Orkney ti Scotland by thi king o thi Danes, Ingrid Leonard, Vilnius, Lithuania

- Klepto, Mark Fiddes, Dubai, UAE

- Keeper, Cian Ferriter, Dublin

- Hare’s Ear, Charlotte Cornell, Whitstable, Kent

- Berwick Street Market, Mon Amour, Kathy Pimlott, London

- Language Therapy, Elena Croitoru, Welling, Kent

- Gold, Julie Hanson, Cedar Rapids, Iowa

- Dun, Robert Walton, Bristol

- Lieutenant Willis writes to his brother, Walter Willis, 6 July 1944, Peter Bakowski, Richmond, Victoria (Australia)

- I’m Hooked On The Jellyfish Live Cam, Julian Bishop, Barnet, Hertfordshire

- The Etymology of Loss, Mary-Jane Holmes, Baldersdale, County Durham

- The Librarian, Kathleen Balma, New Orleans, Louisiana

- Anonymous, Patrick Maddock, Ballykelly, County Wexford

- Four Treasures, Ruth McIlroy, Sheffield

2021 judges’ reports

Linda Gregerson writes…

The great joy of judging such a prize as this is twofold: first, the encounter itself, on the page, with compelling poetic voices, in all their distinctiveness and variety; second, the opportunity for in-depth conversation with a fellow judge about the art form to which we are both devoted. I could not have wished for a finer partner in conversation than John McAuliffe. True gratitude to Anne-Marie Fyfe for giving us the chance to get acquainted, and to all the wonderful poets who provided the substance of our deliberations.

From the Northern Isles to the cornfields of Nebraska, from antiquity to the paradoxical timelessness of the live cam, from the plenitude and bustle of a street market to the stillness of a gable window, the sites and temporalities that occasion the poems in our short list have been bathed in the light of lyric transformation. This is not to say that the tones are always gentle or the vistas reassuring. There is darkness in these pages, as in our world: the suffering of displacement, the treacheries of history, the mortal fallibility of flesh. Anything less would be less convincing. Which is why, I think, I find the poems, each of them, so heartening. The ‘cattle [breathe] out clouds of chaff,’ ‘waters [run] dark / and anti-social,’ the tracks of a lynx are ‘spiderweb laced.’ And a wounded soldier, with the eloquence particular to those whose words are few, writes from hospital to ask about his father’s gravestone. Two thousand twenty-one, and the spectacles of loss are all around us, heightened by the strictures of pandemic; structures we took to be sturdy are ever more endangered. That this much – the compassionate vision and meticulous craftsmanship of this year’s Troubadour poems – shall not have been lost on us is a gift for which I am all the more grateful.

Of our winners in particular:

It is rare indeed that I’m tempted to call a poem ‘perfect.’ Indeed, the term comes dangerously close to stasis and for that reason is not part of my usual canon of praise. But Balthazar quite takes my breath away, and nothing about it is static. Perfect timing, perfect pitch of diction, perfect lineation, perfect tact, and perfect (here’s the miracle) freshness. To one of our most venerable, most ‘handled’ cultural touchstones, the poem brings living breath.

Need to Know brings me close to tears every time I read it. Its questions refuse the diminishment of usual decorum. Spilling over from line to line, eschewing the niceties of punctuation, they immerse us radical precarity. The poem is rigorously tethered to our historical moment: which of us can read it without thinking of migrant crossings in the treacherous Mediterranean and the treacherous English channel? And yet it touches each of us in ways we share with no one and with everyone: which of us can contemplate that ‘you,’ that second person, and not think of our own beloved dead?

The Course to Naming a Brook has also found its footing in direct address. The ‘you’ here is unstable, often disconcerting. It is water, yes, something like the brook of the title in all its manifestations: now conspicuous, now hidden, now silent, now chiefly embodied as noise. We can solve for that. But something about that ‘you’ is more elusive than a buried stream: it modulates, it wants to be a proper interlocutor, it functions as a person might. It breaks the bonds of literary trope.

John McAuliffe writes…

Poets like pattern and coincidence, and reading thousands of poems offers a good deal of scope for generalizing about poetry’s subjects right now, in late 2021, subjects which would not surprise a historian of 2021, year of pandemic. Hospitals, and birdsong, and paintings featured in the general entry, in our initial two hundred poem longlist, and in the winning and shortlisted poems, many of these subjects becoming, as I reflect on the variety of what I read, in fact ways for poems to talk about inheritance and loss, often between generations or even within a family. Formally, the poems were most often first-person accounts, confessions, though some adopted a voice, worked and re-worked to cope with their material, so that distant places or loved ones are imagined with great vividness and colour, last words remembered and taken to heart, a moment in one place made to seem like a resource or stay against loss.

What is it about Sam Garvan’s poem Balthazar which spoke so immediately to me as a reader? Its initial tone is so familiar, but slightly troubled by the sense that the poem is written from the perspective of the tourist time-travelling to Venice, admiring a painting. Until I realised that the poem has gone further away than that, and is in fact written in the voice of one of the painting’s figures, one of the three wise men, Balthazar, this visitor or traveller whose estranged voice has drawn more than one poet to his perspective. Immediately TS Eliot’s atmospheric Journey of the Magi came to mind, a poem itself woven out of the loose ends of a 1620 Christmas sermon delivered by Lancelot Andrewes, the second of a pair of demanding precursors. Somehow, though, this poem holds its own in their company. And I was thinking too, as I read and re-read this poem, of what Joseph Brodsky, self-described Jewish atheist, said about writing a Nativity poem: for him it was a challenge he set himself every year, asking how a poet now might reach after and approach one of the more common points of Western culture, and not be overly daunted by the accretion of images and cliches to its stable scenes.

This poem may have a recognizable scene, but it does contribute original images, and no reader could be unimpressed by the poem’s work, its modulation of line and tone, the detail and clarity of its image-making, ‘the embroidery of ferns / gold light licking the gold cloth’, and that the miracle, when it happens, is nothing like Eliot’s: the stars, when they do arrive, are not a guide, but a suddenness descending among them as snow.

And of course there is no gainsaying that I read this poem on a cold November evening, at a time when its resonance is maybe greater than at other times of the year, as Christmas begins to loom in the distance. The other prize-winning poems likewise benefited from that happenstance of timing, with questions of climate and warming from COP26 debates shaping how I read Need to Know and The Course to Naming a Brook.

Both of these poems have an idiosyncratic purchase on speech and address – who is speaking them, and to whom are they speaking – which seemed to open out into larger conversations going on around us now. In the former, the unidentified relationship between speaker and addressee seems both vividly understood and unmoored from any one location: who has been lost at sea? Who is searching for their body? Is it a child or a parent? The title’s insistence on privacy and on protecting its own knowledge nicely corroborates the poem’s careful elusiveness. And what is personal and heartfelt is also the migrant boat floating in the Channel, or off Lampedusa. Likewise in The Course to Naming a Brook, the speaker is both addressing the pipe which seems to be the stream’s origin, but also recording its need to begin, again and again. We get to see the journey of water, and the changing ways in which a brook redefines how we see a place, all of it irresistibly traced:

The moss wrings itself out and you well in hoof-prints,

smoothing them down and begin your fall again. You let slip

under the elder hedge, hop down a half dozen faezy pools,

as wide as hands pushed into the bank.

The stream’s progress is precarious and it is impossible not to notice the things which get in its way: in this poem, which is delicious to quote, modern developments and something like a folk-song wander before us as the water makes its way with increasing force:

through the houses’ clearcut,

under elder nettle briar, the air full of flight, bees

on the bramble flower and a pair of Cryptic Wood Whites,

who flit out and over the old man’s beard like eloping brides?

I tested what I had read and selected in the company of my fellow judge Linda Gregerson. What made the task we were set a pleasant one was not just these outstanding winning and commended poems but that we found, in many other poems, perfect passages, or unexpected images, or sheer good humour.

2021’s Winning Poems

First Prize, £2,000

Balthazar

after Veronese, Adoration of the Magi, Santa Corona, Vicenza

Oh, I remember the place, of course -

half derelict where it stood

on a storm’s edge.

An old man leaning on his stick.

A mother, child,

fractious at all our retinue arriving,

unsmiling even as they took our gifts.

Behind them cattle breathed out clouds of chaff,

our own mounts restless,

the grooms, their foreign spells and blandishments.

Then Casper knelt down, arms out,

cloak falling round him in the dust,

all its embroidery of ferns,

gold light licking the gold cloth,

he looked for a moment like

a man on fire.

And I remember, more than this,

the road back –

baskets of chestnuts on their heads,

a group of girls, their laughter

rising like a flock of birds,

and then, another night,

a night too long, too cold for sleeping,

suddenly

stars in their thousands

all around

falling like petals from the sky and

snow! the men shouting, snow!

Sam Garvan

__________________________________

Second Prize, £1,000

Need to Know

where did you go in the night was it

dark was it cold where you were out

there on the sea in the night was there

wind did it rain what did you see in

the night on the sea in the rain did you

meet your mother did you see yourself

coming back going under where did you

spend the cold hours before light where did

you go all those years was it cold were you

afraid of the dark the salt water going under

never up could you see were you lonely did

you talk to the stars were there stars or

a moon did you eat were you thirsty

what did you see were you afraid

Geraldine Mitchell

__________________________________

Third Prize, £500

The Course to Naming a Brook

Something like you begins here, as a spring, running

from a pipe, buried through a drystone, brimming

a half-circle cow trough laid into the wall. Overspilt

in limestone silt, moss grown deep, haired with long grass,

you’re a last mammoth, leaning into an era’s end.

Or what I see when I listen to some cellular reverb plying atomic time.

Or random memory. Or a limestone trough, with this man stood in front,

hearing a quiet corner of the Dryhill field, under the Havens’ house.

The moss wrings itself out and you well in hoof-prints,

smoothing them down and begin your fall again. You let slip

under the elder hedge, hop down a half dozen faezy pools,

as wide as hands pushed into the bank. You are only water now,

a membrane wetting the boot-smooth, ragstone path,

before a switch back, down a sheep drove track and disappearance

into your sound’s pooling. You go through the houses’ clearcut,

under elder nettle briar, the air full of flight, bees

on the bramble flower and a pair of Cryptic Wood Whites,

who flit out and over the old man’s beard like eloping brides.

Meadow browns hang down on blood-green dock leaves until it stops.

The wood appears, the light drops and you reveal yourself,

a full twelve strides wide, as a roll-stone rattlebed of ovalled fists.

I wait on the edge of you, for time, in the ash scrub,

where each stem, ivy-clamped in varicose jackets, hangs

heavy with fallaway vine. I listen for your leak-trickle

through barbed wire, into sound in the next clearing.

The bramble push-over waves, crest astral,

blackberry milk-pink flowers, docking with the hive.

From under them, a bedrock surfaces, like a whale’s head,

its skull ridge heavy, stepped downhill in your song’s mirror.

Stream as sound, sound as briar wave, as stone sound,

your polyphony falling faster, louder now, plummetting

the lumpen shelves, like a hurried explanation and making

for the relief of the meadow’s slowing. I clamber into you here,

head for a home in your leaps, where the human path

crosses your stones, scattered and dam-strewn,

turned and turned again in re-arrangement.

From here, where the people start, I look back to your pipe’s dream,

pushing through the drystone, as some anonymous begin-again,

from early rains to slow returns. I’ll call you Haven’s Brook,

and keep to following your way home;

Haven’s to Lime to Frome to Severn,

home to begin again,

Haven’s to Lime to Frome.

Alun Hughes

2021’s Commended Poems

Portraitist

Mr. Rose posed us in the salon with pigeon blood drapes,

then in the geranium-rich patio. The ceramic mural

behind us displayed waves glazed into blue lunettes,

Stella Maris buoying up her son in the crook of her arm.

My sister and I wore plaid skirts, red ribbons in our hair.

Cream turtlenecks creased up where our breasts budded.

He told her to hold my grandmother’s right hand,

told me to place mine on her left shoulder.

Catalan instructions and mother’s translations mixed

with shutter clicks. How he shot family portraits after

his son’s drowning I cannot grasp. How sitters smiled

despite the faulty pool drain, his wife’s qualms before

the school trip. He was childless. We were fatherless.

That afternoon we looked intact. Almost nuclear.

Christina Lloyd

__________________________________

A Shanked Cable

It’s a shanked cable, maybe sliced

by the lads who thinned the trees, or maybe

done a while ago, when a fox,

or squirrel, grubbed it up, and left

the two live wires exposed but not quite touching,

then yesterday’s big downpour filled the gap,

or it rotated in the wind

so that the ends connected, then the surge

took out the breaker and she blew. His words

flow past like streams of last night’s water at

my feet, or like the doctor’s who explained

how acid in the gut, or some small blockage

or just stress can weaken the internal

lining so a tiny twist or shock

can tear it and the contents of the stomach

leak infecting all the other organs.

I nod away without comprehending.

Dumb until he says if he can mend it.

Andrew George

__________________________________

What we take with us and what we leave

Give me the blaze of the day, I hear you say,

or the buzzard riding thermals,

river mist fraying in April sunlight,

the chak chak of the blackbird’s alarm,

the secretive hare bounding from its form;

to which I could reply: frost inside the window-panes,

an east wind scouring bedroom corners,

the hollow drips of thaw – B flat on corrugated iron –

or rain, like today’s, dragooning up the valley

to evict the last fine weather tenant.

One day we too will be gone, make way

for strangers, their renovations and re-builds.

But what if, when time’s up, we simply

bequeath the place to mouse whispers, wind booming

down the flue, the crack and slide of roof flags.

What if we make way for the kestrel in the barn,

leave the garden to the stoat and the owl,

fields to fireweed, gorse and bramble. Who knows

what world awaits our absence, what fauna

might emerge from scrub and thicket.

Mike Barlow

__________________________________

A Table of Green Fields

A man comes home from the market.

He is full of excitement at the new possibilities.

He puts his house keys and his car key down on the table.

He puts two mackerel, spinach and chard.

He lights a candle and puts that on the table.

The sound of Ken splitting logs, the garden stream,

the daffodils, the sun of April—

his friends in the sun at the outdoor table.

He puts the carved white heron on the table,

along with the real heron they saw by the canal.

He puts the disused railway line across

and the river with canoes and voices.

He puts the people on the lower path,

Chris’s injured calf, a conversation

about grey versus dyed hair, his wish

to please everyone on this enchanted morning.

He puts lines from a song: the rhyme of Horace and chorus.

He puts the old name for Cornwall.

He puts the head of a murdered poet.

Then he lays down Spain and all Spain means to him.

He puts the ship to Santander sailing out of Portsmouth,

the caged dogs howling on Deck 10;

the restaurant, a linen tablecloth,

two half bottles of French wine—Côte de Beaune?

He pours its dark clear colour like tawny port

and gives the lie to the waiter about his wife’s

seasickness. Drunkenly he notes: we think

there is a soul but that soul is hard to find.

He puts the Newport gravedigger in Víznar

scrabbling among bones and rocks. . .

he puts a prayer for a night without fear.

He puts clear sea off granite rocks.

He lays out The Hanged Man, The Empress,

The Lovers. Spring rain. The wood’s arousal.

The Padre leaning from an upper wall

like an angel or gargoyle. The blank slate

Tabula rasa of his own Curriculum Vitae.

The creak and drumming of the woodpecker,

the waterfall. Later on, we’re going

to sleep a million years under the marked table.

Christopher Twigg

__________________________________

When I WhatsApp you in San Lorenzo de El Escorial

I am jealous of the hard-boiled series

you watch from your grotty sofa bed,

and of Sunday morning radio programmes,

which make you laugh. I am jealous

of Harry the hedgehog, tattooed on your arm.

Of the Weird Fish T-shirt that nuzzles

your collarbone. The avocadoes

that ripen on your radiator.

The hummingbird hawkmoth, hiding

in your sock. I am jealous of

the San Lorenzo bus stop, where you wait

at seven-thirty, an hour ahead of me.

The spreadsheets on your desk.

The well-off students, who get to hear

your silliness, in the messy office

where you eat vegan hummus on spelt bread.

Of castellana pots at the entrance to your flat.

Of expats, on terraces eating patatas bravas.

I am jealous of the damp patch

in your kitchen. Of your dog, Trasgu,

a name from Asturias meaning goblin:

a well-meaning, yet stubborn goblin.

Yes, I am jealous of Trasgu,

licking your salty feet.

Alexandra Corrin

__________________________________

Beluga, Gravesend

The face it turned to the river:

a salt-water savour,

beautifully uneven

scored, sun-beat, weather-worn.

*

I used to visit a woman here

on grey, uncertain days

when light shivered downwards.

The fields were full of poppies,

the waters ran dark

and anti-social. She coughed up her lungs,

the Thames coughed up coins.

Barges up from the Medway

tore under their canvas like horses.

*

It was summer when the whale came

the fluke of it

a continuous and confused movement against the sky.

*

Where were you born, whale?

To far Cathay, it may be;

obscure ports on the verges of the world.

Sarah Westcott

Note: In 2018, a beluga whale was seen near Gravesend, more than 1,000 miles from its Arctic habitat.

Some lines in this poem are adapted from Rivers of Great Britain. The Thames, from Source to Sea, 1891. Chapter XI – London Bridge to Gravesend.

__________________________________

Ingrid Leonard

__________________________________

Klepto

Dear Greece,

This letter encloses the stone that I stole

from the Theatre of Dionysus on a school trip

to help me with my O’ Level Greek,

understanding the fury of Orestes,

the helplessness of Iphigenia in Taurus.

I was both the hapless brother and sister waiting

for a machine god to rescue my parent’s divorce.

I got a B and my parents got closure

to living sacrifices and the sieges around the house

as I lay with the stone under my pillow

wondering why my religion only had one God

with a son who specialized in suffering

whereas ecstasy specialist Dionysus offered options.

For years the lump hid in an attic box with notes

on eudaimonia from the Nicomachean Ethics.

I got a Beta while my god turned into Bacchus

which has always had its ups and downs.

The English are useless at returning marble

but this lump of Cretaceous limestone is a start.

Please replace it behind the throne of the priest.

Apologies. A place can never have too much magic.

Mark Fiddes

__________________________________

Keeper

Sure I’d best do it myself

the words from your silhouette

at the front door at Crewbawn,

morning light settling around you,

the Boyne beyond, bending the earth.

By the time I follow you out,

arms puckered with stings,

you are high up the alder tree,

head lost in a swarm

of bees, like a man leaning in

through a hatch. Thunderclap

as your box slaps closed,

left neat by the front step

as you recede into the yard.

Later, your dusty red Datsun

pushing off down the avenue,

bees flooding the back window

like coins pouring into a hold.

Cian Ferriter

__________________________________

Hare’s Ear

As I take your keys, I see them there -

butter-bright, fresh-palmed-flat,

each nut-like and star-husked.

Some Latin name. Rare.

Before, when Campion and Catchfly

could be told apart, or Mantle shown

to stop pain, you would know

it only grows when seed-dropped

onto cliffs to lie august-tickled by rain.

It is the grain that secretes into rock,

crag-hiding as the host wings home.

Now, silence has grown. Remember

how you would say we too shouldn’t

settle this far north. Anyway,

youth went with the starlings

and unplanned we learnt to root,

like the bud that rests in your hand.

Minding your step inside, I wonder then if

some overhead murmuration had cried

the words you fumble and lose -

Come home. Choose. Too far.

Sit down, Love. We are a south-bound pair.

Let the Hare’s Ear rest in this jar.

Charlotte Cornell

__________________________________

Berwick Street Market, Mon Amour

Ian the Fish and the pink and white poultry man

and even, once, (ding dong!) that Leslie Phillips

browsing farmed trout and scallops, as though

he ever cooked, were effortlessly the thing, but now

it’s all foil trays for one, those niche intolerances,

confected bonhomie, no melancholy, no arse.

The poultry man, so neatly trussed in his apron strings,

plump as a ballotine, complexion of a Medici cherub,

would probe his cheek with his wicked little tongue

as he gutted chicken, chicken, chicken, fat fingers

in the cavities, pulling down innards, setting aside

livers and tiny hearts. Who knows what became of him?

Ian was felled, first his mother-in-law and then his wife

within the month, and the shine just went off everything.

Mackerel, red mullet, sardines, eyes dulled, began to smell

of fish, which is always a bad sign. And that young man

with the lion’s mane, stacks and flares, the David Bailey

of cauliflower and beetroot, took his truly artistic flash

to Knightsbridge on a promise of glamour and got lost.

Even the bit players, the real fur hat who shot on Sundays

and the huge man-boy in floppy shorts, the type who could

be needled into playing muscle for a pony, were sounder.

All swept away. Leslie Phillips carries on but hasn’t been seen,

at least not by me, ogling the burritos and vegan Bratwurst.

Kathy Pimlott

__________________________________

Language Therapy

The aspen tree feels each one of its leaves

my mother says while searching

for the name of the soft, floral fruit

with plush skin. When she talks

constellations of sunspots move

along her cheekbones.

She says that the missing words are still

in her head, but are not anchored

to the sentences she remembers.

She used to teach this to children who stuttered

because the things they saw

paralysed their tongues.

& when she sits on a bench in a park

she hears aspens speak

& she inhales their chemical language.

Their mute conversations have a bitter tannin

aftertaste. Each name that comes

into her head maintains a space around it

like the tree crowns that break up

the sky. The web of words hanging

in between the day she first saw

her mother as an old woman

& the day they laid her father

into his coffin is unravelling though

she finds shortcuts in her language:

a sycamore leaf becomes a hand,

an ash one becomes a spine.

My mother says she’s getting somewhere,

& all she lost is the order of things

though no one needs it

when they get to the end.

Elena Croitoru

__________________________________

Gold

I haven’t finished with the stillness of the sunflower

when this business with the finch begins.

There is first the visitation, then the waving banner of his dips

through the airspace of three properties.

And now he’s found the metal fence

and lights there. And the metal has silvered, since it’s wet.

And so wet has followed flight as flight has followed flower

in this the sequence of my noticing.

How linear and obvious! There is next and next and next.

That is the way of it. There is rest,

and the impulse to rise from rest; there is contemplation,

and the promise of disturbance.

No element is special, no consequence complete.

On the other hand, it’s possible that that is truer said

the other way around: no element complete. No consequence

is special, though—it’s hard to swallow that.

We have hard memories, and things to blame.

We have our chests of medals.

Julie Hanson

__________________________________

Dun

And sometimes there’s only

that LBJ. You come down

on a February morning, open

the door and it’s there, high

in a bush, you can’t tell where,

but the wiry, tinkling trill

of its call glints, flashes

in the light and snags your ears

and eyes until

you spot it, plump loner

tucked into a tangle

of bramble and singing for all

the world its joy to be dingy,

streaky brown of plumage,

this buff-crowned, tawny

heysogge on the braunche,

drab heg-sugge,

taupe-feathered dike-smowler,

bistre donec, sable

dunoke, plumbeous dunnock,

as if this moment and the bright

radiant sphere of its song

were a wheel of fiery colour, spun

from its throat all time long.

Robert Walton

__________________________________

Lieutenant Willis writes to his brother, Walter Willis, 6 July 1944

I’d rather carry a squealing pig through three cornfields

than write a letter, but here I am, in a military hospital

in Rouen, northern France.

They pulled two bullets out of me.

Had one in the stomach and one in the neck.

I’ve got my appetite back

for breathing and eating unaided.

For a while, Camille was spoon-feeding me.

A nurse here.

She wheels me out to the balcony

when there’s sun.

I’m working my way through

a dog-eared French-English dictionary,

learning the polite words first,

try some out on Camille each day.

You’ll notice I’ve mentioned her twice already.

Confession time. Nurse Agnes, a sharp cookie,

has noticed how I turn my painful neck

to follow Camille’s movements around the ward.

Nurses Agnes has become my language coach.

Patient, but prone to giggling,

she’s been teaching me French terms of endearment.

I’ve got to get the timing, the lightness of tone right,

before asking Camille, “How are you today, my little cabbage?”

Well, that’s the state of play here. Write to me when you can.

Let me know what words you and Aunt Maggie

chose for Pop’s gravestone.

I think of you all, safe in Nebraska.

Peter Bakowski

__________________________________

I’m Hooked On The Jellyfish Live Cam

They rise like smoke in a windless winter,

descend with the languor of summer,

yet they’re a slow-motion spring, budding

and unfurling their tangerines and yellows,

petals billowing around translucent coronas.

Never falling to earth, they berth themselves

in water, each shift a slow-motion ecstasy,

an opening and closing of lips, those seductive

tentacles less soft cotton than electric fences,

hard-wired to stun an oblivious sunfish.

They sleep as they wake in a dream state,

bodiless souls floating in permanent limbo

across the world’s shifting sands. Noiseless,

yet surely they sound a low note: mellow,

a Chet Baker solo, chords long held and lost.

Who wouldn’t envy those who glissade

through life like this, oblivious to the tide, unburdened

by flesh, feathered by pillows of undertow

only to be caught in the arms of themselves?

Slowed-down meteors, they’re more space

than matter, streaming not venom but peace.

Away from the screen, they stay with you,

waxing and waning like rainbows in the mind,

shape-shifting the spirit into self-reflection -

all tops and tails, no eyes yet all eyes, they cast

no shadows, no more than the light streaming

through a high rose window in the sea’s cathedral.

Julian Bishop

__________________________________

The Librarian

The philosophy of life John Ashbery hoped would show up

and infuse his everyday actions with new beliefs is upon me now.

He imagined his would arrive like the big reveal of a Roman

Polanski film in which the protagonist tiptoes through a hidden door

and discovers … what? For Ashbery: a delight in things, ideas,

the gaps between them. For Polanski: sudden hideous knowledge

we aren’t the agents of good we thought we were

but devils, or mothers of devils. Rosemary’s terror face. The resolute

peace that follows a horrific epiphany. Such deep-dyed acceptance

of nightmare scenarios resonates with me, having looked my demons

in the crotch and yelled, You, too, are necessary for a fully-integrated

self! Let’s not have kids together. Of course, living in dread of my id

while I hid behind eco-novels was not a vulnerable act.

It’s what Brené Brown might call “daring faintly,” but

—who am I kidding? There is no but. I need to face my mothering

fears and help Earth at the same time. Okay, but how? Adopt

an orphan sloth with endangered fleas? Teach Esperanto to reluctant

global citizens in Ford trucks? Or just be present in my place

of work to answer any question anyone could ever have

and—failing that—tender some diversion while they search.

That’s one way of tidying up and slinking out. It won’t do.

The ending fits, but the problem persists. Like solving one side

of a Rubix cube and facing it towards the camera. Puzzles

aren’t my forte. Illusions, either. My game is Clue.

The double entendre is wicked: Miss Peacock did it with a lead pipe

in the billiard room. Professor Plum popped in through a secret

passage just in time to witness the deed. Changed his whole manner

of thinking. He wandered around the estate for days, going on about pugs,

cults, trips to the beach … They had to lock him

in a university. Look out! He might still be there. The city is fine

this time of year and books are free. If you keep walking

past the library to the park, you’ll end up in a world of green; half

nature preserve, half golf course. If that soothes then terrifies you,

as it does me, you know the form my parenting will take.

I’d tell you more, but I have a date. I’m going to see a man about a tree.

Kathleen Balma

__________________________________

The Etymology of Loss

loss, n.1

Old Norse, ‘los’ neuter, looseness, ‘breaking up of the ranks of an army’ (Vigfusson)

Somehow in the mêlée, though we swore

to hold our ground, you slipped away, leaving

the accoutrements of war loose in our hands:

the lancets and tanks, the cheval de frise of wires.

In turn, we struck our colours, surrendered

the field to the fields, to willow and sea fret,

to the lift of lapwings, their rise and fall

like fresh linen settling on an empty hospital bed

† loss, n.2

Obsolete. A lynx.

You own the moon at this hour, this hour

of eternal dusk, north of sleep and the wind-

wild mouthings of bur-thistle and fox glove.

The land flattens its ears as you approach

and here am I crouched at the gable window

in the amber eye that is this empty house,

set amongst its gristle of hills, its bell

pits and hushes, seeking out your scent

in the silver pelted shadows beyond the corral

of porchlight that serves as company on nights

like this until the shy light of dawn claws westward

and your tracks retreat dewy and spiderweb laced.

† loss, v.

Scottish. Obsolete. transitive. To unload (a vessel), discharge (goods from a vessel).

Because I am pragmatic, where a heart

used to be I have moored a boat, a coracle

ash-hewn, willow-wickered, its skin taut

and impenetrable, its design such

that it fails to disturb the life it floats

above and is light enough for a child

to throw on her back, walk the rutted path

home, without feeling the weight of it.

Mary-Jane Holmes

__________________________________

Anonymous

An insights and trends specialist could be fetched in:

test the moving waters, lean in to observe the currents.

To stay within the boundaries, no less, when almost anyone

you speak to is getting more and more frustrated about:

being. Quite a few walk to and fro sipping from cups of

single origin coffee. The ambition of one stroller who enjoys

wearing robust boots is to express the complete quandary

in a single timeless quatrain. On a green hill, not far away,

a man in a digger is getting on with his earth works.

We’ve openings up, brief intersections, quick ins and outs.

‘Let’s see this thing that’s been going on’, is the suggestion.

A nine-year-old expresses her wish to ride a Schleich horse

and to make friends with a few Sylvanians. Ever since I was

a child I’ve liked being on the Like List and brushed my teeth

without so much as a moan. But: vigilance. Creatures are

on paw patrol lookout, including domesticated pets.

At this stage, I’m almost ready for happiness in the form

of anonymity, just shuffling along, my less-than-rolling

guitar line offset by a fairly intricate bass, still fit enough

to wipe the shoes of a forthcoming prophet: leaden tempos,

lyrics of despair, no longer express my mild glow-in-the-dark,

almost skeletal presence. I feel enough time has been spent

nursing stubborn old wounds. Remember how the haycock

yielded to the bale’s box shape? And there was frogspawn

in the watering trough. Now there’s no trough. How my

tongue, the industrious ant, once tickled your peony petals?

An explosion in popularity means just what – you’ve been

carefully drawn, having met the respective requirements?

I have a mind for the patchers of lanes for whom there’s less

and less surface left to patch and I appreciate the rain sheen,

its gleam of somewhere else. ‘To find you’re the impact

sub left sitting on the bench,’ a spectator comments. It’s a

hard, yes, it’s a hard: well, bench. At night, on the street,

the laughter segues into silence. The man across has been

leaving much of his downstairs aired because of a problem

in his house: so far, he’s worked from a smell, he’s had

no sightings as such. He takes a brisk one-hour walk three

times a week, achieves a welcome spike. Cones gave way

to rectangles which, in time, made room for massive

straw drums, a territory gathered out of wisps, pitch-forks,

weapons hidden in damp thatch, long-smouldering thoughts;

bronze figures raised up high on plinths or shoved off;

out of minds aroused, arousing themselves, sniffer dogs.

Patrick Maddock

__________________________________

Four treasures

(Fjouwer trekken)

I forgot to them

ik ha fergetten dat ik se hie

then I did not know what were

ik wist net dat

then I did not know to do

en ik wist net wat mei har te dwaan

then I asked them what shall do

(then I asked what shall I)

en ik frege

no answer gjin antwurd

(came through)

Ruth McIlroy